Connectivity brings a broader range of work

Social media platforms connect individuals in ways that often blur the line between work and leisure. Although there has been an increase in the number of employment law cases illustrating the negative aspects of this intersection, there are opportunities within the platforms. In fact, the platforms may constitute new sources of work.

Social media influencers

One example of this type of work is the social media influencer. These are individuals who produce online content (often through social media platforms, such as Instagram and the now defunct Vine). The content consists of short videos or photos that are often comedic. The content aims to speak to an audience in a personal manner; that is, it consists of material that engages with day-to-day aspects of life (in Western countries as the most prominent influencers tend to be based in Western countries). Social media influencers achieve their prominence (as influencers) by the number of followers they have for this online content. Two examples are Amanda Cerny and Lele Pons who have over 23 and 31 million followers (respectively) on Instagram.

If social media influencers are being paid in some form by advertisers, does this make them employees? The likelihood is that social media influencers are not employees. Instead, as discussed in magazines such as Forbes, social media influencers are more often viewed as entrepreneurs. They have established a ‘brand’ in themselves through their capacities to reach a wide audience on information technology platforms. This ‘brand’ is accessed by advertisers seeking unique product placement opportunities. Advertisers are not hiring social media influencers in the orthodox employment way: to undertake paid work under advertisers’ direction, at fixed hours, at a location of the advertiser’s choosing. Instead, advertisers are purchasing exposure opportunities. A clothing advertiser will provide merchandise for a social media influencer to wear as part of online content the influencer produces.

Social media influencers seem to be an example of what has been argued with Uber drivers; that is, the drivers are operating their own businesses and Uber taps into that existing business. In December 2018, the English Court of Appeal ruled that Uber drivers are workers (upholding lower tribunal findings). Still, a dissenting judge of the English Court of Appeal asserted that drivers were not workers but were engaged in a commercial arrangement with the company: ‘Uber drivers at any stage [do not] provide services to [Uber] under a contract with it. The Agreement provides that they do not….’ Leave to appeal to the UK Supreme Court was granted with the Court of Appeal’s decision.

Online labour as embedded within existing employment obligations

Information technology has become embedded in day-to-day of work to such an extent that the topic of social media influencers can be viewed as one of degree. Social media influencers are paid (in some form) for their endorsement (actual or through use) of products. Employees of companies that manufacture goods for public consumption are not necessarily forced to endorse their employers’ products. However, there can be subtle prompting. Any employee may be an influencer within their own network. Corporations that have a public product (merchandise or image) have not overlooked this: ‘we want people(including employees) visiting the … Facebook page and expressing positive sentiments about working for us and about our products.’ (This commercial potential can also create some employment law specific problems.)

Social media has quickly become embedded within work, and, depending upon the industry, may have extended the work day as well as what is viewed as productivity. Consider the following excerpt from British journalist Robert Peston’s book WTF? (London: Hodder, 2017:

‘… the advent of digital has massively increased the amount of work that I expect to do – or am expected by my employers to do – by creating whole new means of distributing my journalism. So in a typical day, along with my television broadcasts …, I would expect to write blogs for ITV’s website and for my Facebook Live page, I would record little video essays for Facebook and Twitter, I would do live broadcasts via Facebook and Periscope and I would put out maybe twenty-odd comments to those who follow me on Twitter. My output and productivity has increased enormously. But I work longer hours, and those hours are busier than they have ever been.’

Putting aside the particularities of journalism for the moment, how many jobs could be described in a similar way due to information technology: productivity has increased but so have the hours of work, which are themselves more intense? While creating online content may not be explicitly mandatory, it is certainly obligatory for a person engaged in her industry. Peston is not necessarily paid to be a social media influencer, but part of his work would seem to oblige him to be have an online presence that draws individuals to his platforms. To that point, who are the online contributors that may be seen as must read people in an industry? There may be particular sources (traditional print newsmedia with online platforms) for this content, but with social media platforms the orthodox source is not a necessary access point.

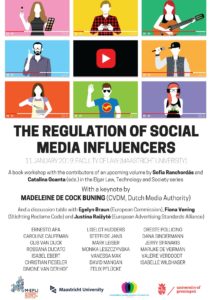

Social Media Influencers is the subject of investigation amongst an international network of scholars.