We live in a digital era where daily life has been significantly changed by the rise of online services and networks. Much of our communication and access to information now takes place in the online world, offering unprecedented possibilities for individual expression and public debate. Judges, just like all citizens, are part of this digital society and increasingly engage by sharing their opinions on social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter (J. JAHN, 137-139).

The aim of this blog post is to address this new phenomenon of judges expressing their views on social media platforms. The significance of judges being able to express themselves on social media is obvious, as it serves the public if judges – as experts and guarantors of the rule of law – comment on social media on matters of public interest. However, judges must always be aware of the interests they could harm. They must find their way within the obvious boundaries of prohibited harmful speech and the rather vague guidelines of their deontological obligations. To clarify the level of protection of judges’ expressions on social media platforms, this blog post will discuss the most recent ruling of the European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’) regarding this topic (the ‘Danilet v Romania case’) and the classification proposed by Judge RĂDULEŢU, hence providing a guideline for judges wishing to express views on matters of public interest on social media. At the end of the blog post, we will link theory and practice by giving a first glimpse of the results of our empirical study on the expression of views on social media by judges of the Belgian Labour courts and tribunals.

Workers’ freedom of expression: the specific case of the judiciary

Article 10(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR’) guarantees everyone the right to freedom of expression. This right includes the freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authorities. Not only is the right to free speech protected against state interference, Article 10 also applies to the work context and horizontal labour relations, including those governed by private law. Indeed, the freedom of expression applies to all individuals, regardless of their employment status. Thus, the protection of citizens’ speech does not end the moment one enters an employment.

The importance of the right to freedom of expression in a democratic society is broadly recognised. However, the fundamental right protected by Article 10 is not absolute and is subject to exceptions. These exceptions must, however, be construed strictly, and the need for any restrictions must be established convincingly. An interference violates Article 10 whenever it fails the ‘three-part test’ of being prescribed by law, being aimed at protecting a legitimate interest and being necessary in a democratic society (Article 10(2) ECHR). To assess the necessity of an interference in a democratic society, a balancing exercise must be conducted, weighing the different interests at stake.

It is clear that this requirement to balance the different interests at stake also extends to the employment context. Indeed, an employee’s free speech is not absolute and may be restricted because of the necessities of the undertaking, such as the protection of the employer’s business reputation. The ECtHR recognises that “even if the requirement to act in good faith in the context of an employment contract does not imply an absolute duty of loyalty towards the employer or a duty of discretion to the point of subjecting the worker to the employer’s interests, certain manifestations of the right to freedom of expression that may be legitimate in other contexts are not legitimate in that of labour relations.”Although criticism on the horizontal application of the ‘three-part test’ in labour relationships can be formulated (O. DE SCHUTTER, 118-139), the balance between the employee’s fundamental rights and the employer’s business interests, and the resulting duty of loyalty and discretion required of the employee, may ultimately lead to restrictions on the employee’s free speech.

In the case of civil servants, this is particularly so, since the very nature of civil service requires a civil servant to be bound by a duty of loyalty and discretion. This is certainly true for the judiciary, a distinct category of civil servants, who have the duty to guarantee the existence of the rule of law and to assure the citizen’s confidence in the judiciary. There is no doubt that judges enjoy the right to freedom of expression, regardless of their function (Wille v Liechtenstein). However, given their specific role as the guarantor of justice, judges must assure their impartiality and authority and can therefore be expected to exercise their freedom of expression with restraint. A judge’s role and the associated duties and responsibilities can therefore justify restricting the judge’s individual freedom of expression. On the other hand, it can lead to a heightened protection of the expression and even to a duty to speak, for example when the expression is crucial to the protection of democratic values.

Even though the judiciary’s deontological obligations fulfil a specific aim and can therefore justify a limitation on the freedom of expression, any interference with judges’ freedom of expression must still be prescribed by law, pursue a legitimate aim, and be necessary in a democratic society. To assess whether the last condition has been fulfilled, the ECtHR examines the proportionality of the interference to the legitimate aim pursued and the relevance and sufficiency of the justification adduced by the national authorities by bringing together different criteria on a weighting scale. This balancing exercise ultimately determines the level of protection of the expression concerned. Member states have a certain margin of appreciation in determining whether an interference with the freedom of expression of judges is proportionate. Nonetheless, having regard to the increasing importance attached to the separation of powers and the need to preserve the independence of the judiciary, any interference with the exercise of a judge’s freedom of expression must be examined carefully.

What about judges’ freedom of expression on social media? A recent recap in the Danilet case

In light of democracy and the separation of powers, the European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’) attaches great importance to the freedom of expression of the judiciary when expressions relate to matters of public interest. This is certainly the case in today’s digitalised world, where the internet offers unprecedented means of informing and interacting with the public on important issues. On the other hand, it also entails risks as communication that was intended to stay private can easily be picked up and start a whole own -public- life. When judges express views on social media, the authority and impartiality of the judiciary could therefore be at risk.

In a recent ruling of 20 February 2024, the ECtHR emphasised once more that judges’ freedom of expression requires a complex balancing exercise, and that this is no different when views are expressed on social media. Whenever an interference with the freedom of speech of a judge is established, the ECtHR must strike a fair balance between the legitimate interest of the state in ensuring the proper functioning of the judiciary and the judge’s fundamental right to free speech. As mentioned above, judges can be expected to exercise their freedom of expression with restraint, given their specific role. However, much depends on the type of expression and the hierarchical position of the judge, but also on other criteria such as the context of the expression and the chilling effect, aspects that cumulatively define the ultimate protection granted to a specific expression.

In the aforementioned Danilet v Romania case, a judge had shared his views on, amongst others, the government’s influence on public institutions. He expressed his criticism in strong language and did so on his publicly accessible Facebook account, which had around 50,000 subscribers. A disciplinary investigation was initiated, and as a result, a 2 months’ salary reduction of 5% was imposed for compromising the honour and image of the judiciary and for failing to adhere to the obligation of discretion. Judge Danilet did not agree with this disciplinary measure and took the case to the Strasbourg Court. The ECtHR reiterated its jurisprudential guidelines on judges’ freedom of speech. This again made clear that even though there is little scope under Article 10 for restrictions on political speech or on debate of questions of public interest by ‘ordinary’ citizens, judges must accept different limitations on their free speech because of their employment status.

With regard to the protection of views expressed by judges, a distinction must be made between expressions on matters of public interest -as in the Danilet case-, expressions related to the judicial decision-making sphere, and expressions related to the judge’s individual sphere. The degree of protection given to each of these types of expressions varies. This blog post will not comment on expressions related to the judicial decision-making sphere and expressions related to the judge’s individual sphere but will only discuss views expressed by judges on matters of public interest. Indeed, this type of expression constitutes a particularly interesting category in the case of the judiciary, as is also demonstrated by the Danilet case. The degree of protection given to a judge’s expression on a matter of public interest namely varies according to, among others, the function of the judge. This is why, based on the concurring opinion by Judge RĂDULEŢU in the Danilet case, a distinction within the category of expressions on matters of public interest can be proposed, depending on the specific topic and the profile of the speaker. Each category is associated with a distinct set of applied principles, resulting in a different degree of protection:

- First, there are the general principles concerning the exercise of freedom of expression, which apply to individuals participating in debates of general interest. These principles still apply even though the speaker is also a judge. Expressions of this sort enjoy a strong protection. In cases where these rules apply, the ECtHR must conduct a rigorous proportionality review, and the national authorities only have a narrow margin of appreciation.

- Second, there are the specific principles concerning the exercise of freedom of expression by civil servants in general and judges in particular, who are bound by a duty of reserve. This duty requires civil servants to avoid any action that could undermine public confidence in the impartiality of the public service. It obliges civil servants to exercise moderation in expressing their personal opinions in public and to avoid actions that might compromise the honour and dignity of their office. This duty applies not only to comments concerning their specific public service but also to broader societal debates, whether expressed within or outside the workplace. Therefore, to safeguard the authority and impartiality of the judiciary and to protect the public confidence in the judiciary against destructive attacks, judges’ freedom of expression may be restricted. Indeed, judges are expected to conduct themselves in such a way as to uphold the dignity of their office and the impartiality and independence of the judiciary, both in and outside the context of their employment. A judge’s words are namely perceived as an expression of an objective assessment that is binding not only for the person speaking but also for the entire institution of justice they represent, thus justifying restrictions. In this regard, Member States have a certain degree of discretion. However, since the principles governing this category represent an exception to the general principles, they must be interpreted restrictively. The scope of the duty of reserve cannot be interpreted more broadly to include any expression of judges on matters of public interest, reason why the general principles applicable to individuals also apply to judges. To date, the ECtHR has limited the application of these specific rules to situations in which a judge has expressed views likely to undermine the authority and independence of the judiciary, especially when those views concern the functioning of the judicial system.

- Third, there are the specific principles concerning the exercise of freedom of expression of judges who occupy a prominent position in the hierarchy and speak about the functioning of the judicial system and the independence of the judiciary. Judges who comment on matters of public interest not only in their personal capacity, but also as representative of the judiciary, will enjoy a heightened protection. These judges’ freedom of expression even becomes a duty to speak if the fundamental values of the rule of law and judicial independence come under threat.

In the Danilet case, the ECtHR ruled that there was indeed a violation of Article 10 ECHR. The general principles applied to the Facebook messages because Mr Danilet did not occupy a high position in the hierarchy. Furthermore, he had expressed his opinions on a matter of public interest pertaining to the separation of powers and the importance of maintaining the autonomy of institutions in a democratic state, but not directly related to the functioning of justice. The principles applicable to individuals participating in debates of general interest thus applied, resulting in a narrow margin of appreciation. However, the ECtHR’s decision was only reached by a majority of four against three. The dissenting Judges KUCSKO-STADLMAYER, EICKE and BORMANN disagreed, among other things, with the application of the general principles and the strict proportionality test in this case. They held that Mr Danilet, given the absence of a high hierarchical position and the fact that he was not a whistleblower, should have been regarded as a judge with a duty of discretion to safeguard the authority and impartiality of the judiciary and not as an individual participating in debates of public interest. They thus seemed to disagree with the introduction of a ‘general principles’ category in the case of the judiciary, leaving room only for the protection of judges’ freedom of expression as judges with a duty of discretion or as judges with a high hierarchical position. This concurring opinion suggests that there still seems to be disagreement about the extent to which deontological obligations can restrict judges’ freedom of expression.

The above-mentioned classification equally applies to views expressed on traditional media outlets and on social media platforms. The social media context does not change the fact that a balance must be sought between the different interests at stake. However, the effects of exercising one’s right to freedom of expression on social media can alter the balance. As mentioned, social media namely entails the risk of reaching a very broad audience, while the duty of discretion requires a judge to exercise free speech with reserve. Therefore, when balancing the various interests involved, the message’s reach can be considered, which may eventually tip the balance in favour of the state’s interests. For example, in the first case where the ECtHR had to rule on a situation in which a judge had expressed views on social media, i.e. Kozan v Turkey, the ECtHR concluded that there had been a violation of Article 10 ECHR and, to reach this conclusion, had specifically considered the fact that the judge had shared an article in a closed Facebook group for legal professionals, that the group did not appear in internet search engines, and that the message was not shared with the general public as a result. However, in the Danilet v Romania case, where the judge did not limit his messages to a specific group of viewers, the Court stated that the judge took some risks, but did not share statements that were clearly unlawful, defamatory, hateful or inciting to violence. The reach of the message therefore did not ultimately alter the scale. The public interest topic and the absence of a harmful character seemed to have taken the lead, leaving the social media context to be one of the criteria to consider when assessing the necessity of an interference in a democratic society, without changing the importance of the expression’s subject matter and the speaker’s function.

So far, the ECtHR has only had the opportunity to decide on judges’ free speech on social media concerning expressions that related to matters of public interest. However, it is reasonable to assume that the ECtHR’s guiding principles concerning expressions related to a judge’s private sphere and to the judicial-decision making sphere, as established in cases where judges expressed themselves in traditional media, will also apply to judges’ free speech on social media. This would mean that judges are required to exercise maximum restraint when views are related to judicial proceedings, while there is more leeway regarding expressions relating to the private sphere, as long as the authority and impartiality of the judiciary are not jeopardised.

In conclusion, when judges wish to exercise their freedom of expression on social media, they must navigate within the limits of their deontological obligations and the established jurisprudential guidelines.

Theory into practice: an empirical study

As is often the case in the field of law, the theory builds on a (limited) number of cases that have reached the effective examination by courts. Although this theory ought to guide practice, it is not always evident whether this actually happens. To examine the effective translation of the guiding principles in practice, a preliminary pilot survey was conducted among a heterogenous group of 41 judges at the Belgian labour courts and tribunals.[i] Prior to discussing two specific questions that have been asked to the respondents, it should be noted that this blog post only covers a small aspect of the conducted study. An extensive analysis will be provided in our future research. This study’s primary goal is to encourage debate on judges’ freedom of speech on social media and to stimulate more research on the topic while making no claims to be able to draw broad conclusions.

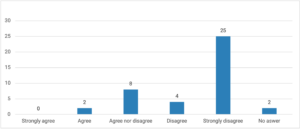

The case of Danilet v Romania once again demonstrated that the protection of an expression is dependent upon the expression’s subject matter and the speaker’s profile. However, not all survey respondents seemed to agree with these guidelines. When asked whether judges’ freedom of expression on social media should be differently protected depending on the hierarchical position of the speaker (see figure 1), more than half of the respondents mentioned they strongly disagreed with this statement. Almost one third of the respondents indicated they disagreed or agreed nor disagreed. Most of the respondents thus disagreed to a greater or lesser extent with a different protection of an expression depending on the hierarchical position of the speaker, even though the ECtHR assesses judges’ freedom of expression according to this principle.

Figure 1

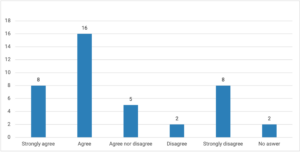

In contrast, when asked whether the protection of a judge’s expression on social media should depend on the subject matter of the expression (see figure 2), half of the respondents mentioned they strongly agreed or agreed with the statement. A few respondents neither agreed nor disagreed, and one fourth of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed. The respondents’ opinions are more divided regarding this guideline, although a majority agrees with a different level of protection of an expression depending on the expression’s topic.

Figure 2

Taken together, these results[ii] suggest that the respondents do not completely agree with the ECtHR’s guiding principles. And not only in the survey, but also within the ECtHR, there appears to be no consensus on the applicable principles, as evidenced by the dissenting opinion in Danilet v Romania and in the partly dissenting, partly concurring opinion in Zurek v Poland. This would seem to suggest that the extent to which deontological obligations affect judges’ freedom of expression (on social media) is not yet set in stone, and the balance could still shift.

________________________

References

[i] How the respondents manoeuvre between the limits of their deontological obligations when sharing opinions on social media and how they perceive the impact of these deontological obligations on their freedom of expression, will be discussed further in our future research. Our aim is to publish an article in a special issue of the European Labour Law Journal in early 2025.

[ii] Respondents who did not fill in more than 75% of the survey were removed from the data analysis. The final group consisted of 41 respondents (N=41).

I believe judges have the exact same rights. They shouldn’t mention specific cases but they for sure can give their opinion. In fact I believe it’s very much necessary for us to be able to read opinions from people who actually know what they are talking about.