To date the debate on the “future of work” and technology has predominantly concentrated on the quantity of jobs that will be lost or gained because of automation. While this is certainly important, we should also be concerned about the quality of the jobs we are creating.

Over the past few weeks, the news has been full of stories related to the “future of work”. Stories spanned from the Employment Appeal Tribunal judgment confirming the “worker” status of Uber drivers in the UK, to the decision in the same country denying Deliveroo riders collective rights under UK law; from the strike of Deliveroo riders in Brussels and Brighton to that of Italian and German workers in Amazon warehouses.

These apparently diverse events all have major points in common. For a start, they concern services that are popular among customers, delivered with impressive speed through the use of digital technologies. Apps and online platforms, whether to make purchases online or to have food delivered to our homes, feel almost like “magic” for their speedy and seamless operations. It is thus no surprise that they are cherished as a great perk of modernity. They also offer job opportunities to many workers and are praised for boosting employment and economic growth. Yet they prompt fundamental questions about labour issues.

The fact that these goods and services are ordered and paid online, as well as their speed and customer-driven efficiency, can give the wrong impression that these services are entirely automatized and digital, with humans playing scarce or no role in delivering what we want at the click of a mouse or a tap on our phones.

The recent articles in the news offer us a different reality and claim back our attention to the less glittering working conditions of the people delivering these services. Either by litigation or by direct collective action, these workers remind us that behind the “techy” façade of digital services, not all the work is done by smart software or futuristic robots – human labour is essential for keeping the wheels of digital platforms turning. And it is not just highly skilled work of tech programmers and computer scientists. It is often hard physical work – sometimes hazardous, such as cycling around busy city centres to deliver food; sometimes fatiguing, like picking and packing online-purchased items in a warehouse in timed increments.

Of course, technology is still fundamental in shaping how this work is performed, but it does not play the same liberating role that we as customers imagine. For workers, digital tools are used continuously to direct and measure their performance.

Amazon workers are directed by their digital scanners to pick the items that are placed at random in the warehouse. Digital tools also calculate and dictate the seconds they should spend in picking the following article and measure how many items are processed in a given hour. Often, these tools are “wearable” – devised to be worn by workers and to guide and follow them through GPS at any time during work.

Delivery riders and ride-sharing drivers are assigned to the next task by the app’s algorithms, which are also designed to measure the speed and diligence of the worker in completing the tasks, also by factoring in the rating and reviews that customers assign to workers. Bad scores or a performance below the algorithm’s standards can lead to the exclusion of the worker from the platform and, thus, to a “dismissal”, also made easier by the purported self-employment status of these workers. And this is not confined to tasks “on-the-road”. Workers on online “freelancing marketplaces” and domestic workers who are contracted on platforms to do work in customers’ households live in constant worry over ratings and how the platforms’ algorithm take ratings into account when assigning the next job.

Technological tools are therefore used to direct and monitor the performance of individual workers in what, rather than a utopian “future of work”, seems to be 20th century Taylorism reloaded.

The central question then is how to ensure that the technological and managerial advancements that facilitate our lives as customers do not come at the expenses of the workers who make these services possible.

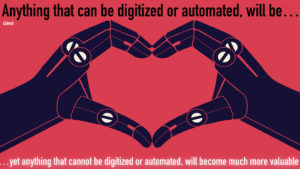

Besides engaging in more or less sophisticated guesses on how many jobs will be automated, therefore, we need to focus on the quality of present and future jobs. This also is a refreshing perspective for labour specialists – as we are told continuously that tech advances will put human labour out of work. Now we realise that humans at work are here to stay, but so are many old labour challenges.

Since technology allows for more and more scalable workforces and just-in-time practices, it is vital to ensure that this does not come at the price of increased precariousness and instability of work and income for workers. Securing predictable and decent work and income will be the biggest challenge for employment and social protection systems. Also – and, as importantly – the impact of technological breakthroughs and “management by algorithm” on workers and working conditions must be monitored and employers made accountable.

Regulation is fundamental for addressing these challenges. It is needed to govern the process of collecting, storing and – if necessary – destroying data obtained from human labour, making sure that what remains is respectful of the human dignity of individual workers. It is needed to control the use of the data collected and how these data are translated into managerial decisions concerning workers. Limiting the invasiveness of data collection will also be necessary – boundaries must be set, beyond which data collection, even if technically possible, is not allowed. Technological innovation cannot be an excuse to introduce mass surveillance at the workplace.

Regulation will also have to ensure that any assessment of workers’ performance, whether based on customers’ rating or other work metrics, remain accountable and that humans oversee and are responsible for any software-suggested measure that affect individual workers.

In turn, software must be programmed to ensure transparency and exclude arbitrariness and discriminatory behaviours. This is all the more necessary during recruitment processes since algorithms and computer programs are ever more used for the selection of workers. Rating systems must also be made fully transparent and fair, making sure that capricious and discriminatory ratings are not given any weight. Moreover, ratings should be “portable”, allowing workers who desire to do so to bring their positive ratings with them if they change platforms or to refer to them when looking for other jobs.

It goes without saying that regulation in these fields will have to remain flexible and quickly adaptable to technological innovation. For this reason, besides a general default legislative framework, specific and bespoke regulation is essential. In this regard, collective bargaining can play a primary role both at the sectoral and at the workplace level. Collective agreements could address the use of digital technology, data collection and algorithms that direct and discipline the workforce, ensuring transparency, social sustainability and compliance of these practices with regulation. “Negotiating the algorithm” must become a central objective for trade unions and responsible employers. UNI Global Union, for instance, advanced extremely compelling proposals that go in the direction of sound “social dialogue on the algorithm”. Governments should encourage these efforts, also using fiscal incentives, and prohibit unsustainable technological and business practices. It will not be a simple process or a quick one, but it is what we need to ensure that the benefits of technology improve our societies.